Content from Introducing Databases and SQL

Last updated on 2023-04-21 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is a relational database and why should I use it?

- What is SQL?

Objectives

- Describe why relational databases are useful.

- Create and populate a database from a text file.

- Define SQLite data types.

Setup

Note: this should have been done by participants before the start of the workshop.

We use DB Browser for SQLite and the Portal Project dataset throughout this lesson. See Setup for instructions on how to download the data, and also how to install DB Browser for SQLite.

Motivation

To start, let’s orient ourselves in our project workflow. Previously, we used Excel and OpenRefine to go from messy, human created data to cleaned, computer-readable data. Now we’re going to move to the next piece of the data workflow, using the computer to read in our data, and then use it for analysis and visualization.

What is SQL?

SQL stands for Structured Query Language. SQL allows us to interact with relational databases through queries. These queries can allow you to perform a number of actions such as: insert, select, update and delete information in a database.

Dataset Description

The data we will be using is a time-series for a small mammal community in southern Arizona. This is part of a project studying the effects of rodents and ants on the plant community that has been running for almost 40 years. The rodents are sampled on a series of 24 plots, with different experimental manipulations controlling which rodents are allowed to access which plots.

This is a real dataset that has been used in over 100 publications. We’ve simplified it for the workshop, but you can download the full dataset and work with it using exactly the same tools we’ll learn about today.

Questions

Let’s look at some of the cleaned spreadsheets you downloaded during Setup to complete this challenge. You’ll need the following three files:

surveys.csvspecies.csvplots.csv

Challenge

Open each of these csv files and explore them. What information is contained in each file? Specifically, if I had the following research questions:

- How has the hindfoot length and weight of Dipodomys species changed over time?

- What is the average weight of each species, per year?

- What information can I learn about Dipodomys species in the 2000s, over time?

What would I need to answer these questions? Which files have the data I need? What operations would I need to perform if I were doing these analyses by hand?

Goals

In order to answer the questions described above, we’ll need to do the following basic data operations:

- select subsets of the data (rows and columns)

- group subsets of data

- do math and other calculations

- combine data across spreadsheets

In addition, we don’t want to do this manually! Instead of searching for the right pieces of data ourselves, or clicking between spreadsheets, or manually sorting columns, we want to make the computer do the work.

In particular, we want to use a tool where it’s easy to repeat our analysis in case our data changes. We also want to do all this searching without actually modifying our source data.

Putting our data into a relational database and using SQL will help us achieve these goals.

Definition: Relational Database

A relational database stores data in relations made up of records with fields. The relations are usually represented as tables; each record is usually shown as a row, and the fields as columns. In most cases, each record will have a unique identifier, called a key, which is stored as one of its fields. Records may also contain keys that refer to records in other tables, which enables us to combine information from two or more sources.

Databases

Why use relational databases

Using a relational database serves several purposes.

- It keeps your data separate from your analysis.

- This means there’s no risk of accidentally changing data when you analyze it.

- If we get new data we can rerun the query.

- It’s fast, even for large amounts of data.

- It improves quality control of data entry (type constraints and use of forms in MS Access, Filemaker, Oracle Application Express etc.)

- The concepts of relational database querying are core to understanding how to do similar things using programming languages such as R or Python.

Database Management Systems

There are different database management systems to work with relational databases such as SQLite, MySQL, PostgreSQL, MSSQL Server, and many more. Each of them differ mainly based on their scalability, but they all share the same core principles of relational databases. In this lesson, we use SQLite to introduce you to SQL and data retrieval from a relational database.

Relational databases

Let’s look at a pre-existing database, the

portal_mammals.sqlite file from the Portal Project dataset

that we downloaded during Setup. Click on the

“Open Database” button, select the portal_mammals.sqlite file, and click

“Open” to open the database.

You can see the tables in the database by looking at the left hand

side of the screen under Database Structure tab. Here you will see a

list under “Tables.” Each item listed here corresponds to one of the

csv files we were exploring earlier. To see the contents of

any table, right-click on it, and then click the “Browse Table” from the

menu, or select the “Browse Data” tab next to the “Database Structure”

tab and select the wanted table from the dropdown named “Table”. This

will give us a view that we’re used to - a copy of the table. Hopefully

this helps to show that a database is, in some sense, just a collection

of tables, where there’s some value in the tables that allows them to be

connected to each other (the “related” part of “relational

database”).

The “Database Structure” tab also provides some metadata about each

table. If you click on the down arrow next to a table name, you will see

information about the columns, which in databases are referred to as

“fields,” and their assigned data types. (The rows of a database table

are called records.) Each field contains one variety or type of

data, often numbers or text. You can see in the surveys

table that most fields contain numbers (BIGINT, or big integer, and

FLOAT, or floating point numbers/decimals) while the

species table is entirely made up of text fields.

The “Execute SQL” tab is blank now - this is where we’ll be typing our queries to retrieve information from the database tables.

To summarize:

- Relational databases store data in tables with fields (columns) and records (rows)

- Data in tables has types, and all values in a field have the same type (list of data types)

- Queries let us look up data or make calculations based on columns

Database Design

- Every row-column combination contains a single atomic value, i.e., not containing parts we might want to work with separately.

- One field per type of information

- No redundant information

- Split into separate tables with one table per class of information

- Needs an identifier in common between tables – shared column - to reconnect (known as a foreign key).

Import

Before we get started with writing our own queries, we’ll create our

own database. We’ll be creating this database from the three

csv files we downloaded earlier. Close the currently open

database (File > Close Database) and then follow

these instructions:

- Start a New Database

- Click the New Database button

- Give a name and click Save to create the database in the opened folder

- In the “Edit table definition” window that pops up, click cancel as we will be importing tables, not creating them from scratch

- Select File >> Import >> Table from CSV file…

- Choose

surveys.csvfrom the data folder we downloaded and click Open. - Give the table a name that matches the file name

(

surveys), or use the default - If the first row has column headings, be sure to check the box next to “Column names in first line”.

- Be sure the field separator and quotation options are correct. If you’re not sure which options are correct, test some of the options until the preview at the bottom of the window looks right.

- Press OK, you should subsequently get a message that the table was imported.

- Back on the Database Structure tab, you should now see the table listed. Right click on the table name and choose Modify Table, or click on the Modify Table button just under the tabs and above the table list.

- Click Save if asked to save all pending changes.

- In the center panel of the window that appears, set the data types

for each field using the suggestions in the table below (this includes

fields from the

plotsandspeciestables also). - Finally, click OK one more time to confirm the operation. Then click the Write Changes button to save the database.

| Field | Data Type | Motivation | Table(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| day | INTEGER | Having data as numeric allows for meaningful arithmetic and comparisons | surveys |

| genus | TEXT | Field contains text data | species |

| hindfoot_length | REAL | Field contains measured numeric data | surveys |

| month | INTEGER | Having data as numeric allows for meaningful arithmetic and comparisons | surveys |

| plot_id | INTEGER | Field contains numeric data | plots, surveys |

| plot_type | TEXT | Field contains text data | plots |

| record_id | INTEGER | Field contains numeric data | surveys |

| sex | TEXT | Field contains text data | surveys |

| species_id | TEXT | Field contains text data | species, surveys |

| species | TEXT | Field contains text data | species |

| taxa | TEXT | Field contains text data | species |

| weight | REAL | Field contains measured numerical data | surveys |

| year | INTEGER | Allows for meaningful arithmetic and comparisons | surveys |

You can also use this same approach to append new fields to an existing table.

Adding fields to existing tables

- Go to the “Database Structure” tab, right click on the table you’d like to add data to, and choose Modify Table, or click on the Modify Table just under the tabs and above the table.

- Click the Add Field button to add a new field and assign it a data type.

Data types

| Data type | Description |

|---|---|

| CHARACTER(n) | Character string. Fixed-length n |

| VARCHAR(n) or CHARACTER VARYING(n) | Character string. Variable length. Maximum length n |

| BINARY(n) | Binary string. Fixed-length n |

| BOOLEAN | Stores TRUE or FALSE values |

| VARBINARY(n) or BINARY VARYING(n) | Binary string. Variable length. Maximum length n |

| INTEGER(p) | Integer numerical (no decimal). |

| SMALLINT | Integer numerical (no decimal). |

| INTEGER | Integer numerical (no decimal). |

| BIGINT | Integer numerical (no decimal). |

| DECIMAL(p,s) | Exact numerical, precision p, scale s. |

| NUMERIC(p,s) | Exact numerical, precision p, scale s. (Same as DECIMAL) |

| FLOAT(p) | Approximate numerical, mantissa precision p. A floating number in base 10 exponential notation. |

| REAL | Approximate numerical |

| FLOAT | Approximate numerical |

| DOUBLE PRECISION | Approximate numerical |

| DATE | Stores year, month, and day values |

| TIME | Stores hour, minute, and second values |

| TIMESTAMP | Stores year, month, day, hour, minute, and second values |

| INTERVAL | Composed of a number of integer fields, representing a period of time, depending on the type of interval |

| ARRAY | A set-length and ordered collection of elements |

| MULTISET | A variable-length and unordered collection of elements |

| XML | Stores XML data |

SQL Data Type Quick Reference

Different databases offer different choices for the data type definition.

The following table shows some of the common names of data types between the various database platforms:

| Data type | Access | SQLServer | Oracle | MySQL | PostgreSQL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| boolean | Yes/No | Bit | Byte | N/A | Boolean |

| integer | Number (integer) | Int | Number | Int / Integer | Int / Integer |

| float | Number (single) | Float / Real | Number | Float | Numeric |

| currency | Currency | Money | N/A | N/A | Money |

| string (fixed) | N/A | Char | Char | Char | Char |

| string (variable) | Text (<256) / Memo (65k+) | Varchar | Varchar2 | Varchar | Varchar |

| binary object OLE Object Memo Binary (fixed up to 8K) | Varbinary (<8K) | Image (<2GB) Long | Raw Blob | Text Binary | Varbinary |

Keypoints

- SQL allows us to select and group subsets of data, do math and other calculations, and combine data.

- A relational database is made up of tables which are related to each other by shared keys.

- Different database management systems (DBMS) use slightly different vocabulary, but they are all based on the same ideas.

Content from Accessing Data With Queries

Last updated on 2023-04-21 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do I write a basic query in SQL?

Objectives

- Write and build queries.

- Filter data given various criteria.

- Sort the results of a query.

Writing my first query

Let’s start by using the surveys table. Here we have data on every individual that was captured at the site, including when they were captured, what plot they were captured on, their species ID, sex and weight in grams.

Let’s write an SQL query that selects all of the columns in the surveys table. SQL queries can be written in the box located under the “Execute SQL” tab. Click on the right arrow above the query box to execute the query. (You can also use the keyboard shortcut “Cmd-Enter” on a Mac or “Ctrl-Enter” on a Windows machine to execute a query.) The results are displayed in the box below your query. If you want to display all of the columns in a table, use the wildcard *.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys;We have capitalized the words SELECT and FROM because they are SQL keywords. SQL is case insensitive, but it helps for readability, and is good style.

If we want to select a single column, we can type the column name instead of the wildcard *.

SQL

SELECT year

FROM surveys;If we want more information, we can add more columns to the list of fields, right after SELECT:

SQL

SELECT year, month, day

FROM surveys;Limiting results

Sometimes you don’t want to see all the results, you just want to get

a sense of what’s being returned. In that case, you can use a

LIMIT clause. In particular, you would want to do this if

you were working with large databases.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

LIMIT 10;Unique values

If we want only the unique values so that we can quickly see what

species have been sampled we use DISTINCT

SQL

SELECT DISTINCT species_id

FROM surveys;If we select more than one column, then the distinct pairs of values are returned

SQL

SELECT DISTINCT year, species_id

FROM surveys;Calculated values

We can also do calculations with the values in a query. For example, if we wanted to look at the mass of each individual on different dates, but we needed it in kg instead of g we would use

SQL

SELECT year, month, day, weight/1000

FROM surveys;When we run the query, the expression weight / 1000 is

evaluated for each row and appended to that row, in a new column. If we

used the INTEGER data type for the weight field then

integer division would have been done, to obtain the correct results in

that case divide by 1000.0. Expressions can use any fields,

any arithmetic operators (+, -,

*, and /) and a variety of built-in functions.

For example, we could round the values to make them easier to read.

SQL

SELECT plot_id, species_id, sex, weight, ROUND(weight / 1000, 2)

FROM surveys;SQL

SELECT day, month, year, species_id, weight * 1000

FROM surveys;Filtering

Databases can also filter data – selecting only the data meeting

certain criteria. For example, let’s say we only want data for the

species Dipodomys merriami, which has a species code of DM. We

need to add a WHERE clause to our query:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

WHERE species_id='DM';We can do the same thing with numbers. Here, we only want the data since 2000:

SQL

SELECT * FROM surveys

WHERE year >= 2000;If we used the TEXT data type for the year, the

WHERE clause should be year >= '2000'.

We can use more sophisticated conditions by combining tests with

AND and OR. For example, suppose we want the

data on Dipodomys merriami starting in the year 2000:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

WHERE (year >= 2000) AND (species_id = 'DM');Note that the parentheses are not needed, but again, they help with

readability. They also ensure that the computer combines

AND and OR in the way that we intend.

If we wanted to get data for any of the Dipodomys species,

which have species codes DM, DO, and

DS, we could combine the tests using OR:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

WHERE (species_id = 'DM') OR (species_id = 'DO') OR (species_id = 'DS');SQL

SELECT day, month, year, species_id, weight / 1000

FROM surveys

WHERE (plot_id = 1) AND (weight > 75);Building more complex queries

Now, let’s combine the above queries to get data for the 3

Dipodomys species from the year 2000 on. This time, let’s use

IN as one way to make the query easier to understand. It is equivalent

to saying

WHERE (species_id = 'DM') OR (species_id = 'DO') OR (species_id = 'DS'),

but reads more neatly:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

WHERE (year >= 2000) AND (species_id IN ('DM', 'DO', 'DS'));We started with something simple, then added more clauses one by one, testing their effects as we went along. For complex queries, this is a good strategy, to make sure you are getting what you want. Sometimes it might help to take a subset of the data that you can easily see in a temporary database to practice your queries on before working on a larger or more complicated database.

When the queries become more complex, it can be useful to add

comments. In SQL, comments are started by --, and end at

the end of the line. For example, a commented version of the above query

can be written as:

SQL

-- Get post 2000 data on Dipodomys' species

-- These are in the surveys table, and we are interested in all columns

SELECT * FROM surveys

-- Sampling year is in the column `year`, and we want to include 2000

WHERE (year >= 2000)

-- Dipodomys' species have the `species_id` DM, DO, and DS

AND (species_id IN ('DM', 'DO', 'DS'));Although SQL queries often read like plain English, it is always useful to add comments; this is especially true of more complex queries.

Sorting

We can also sort the results of our queries by using

ORDER BY. For simplicity, let’s go back to the

species table and alphabetize it by taxa.

First, let’s look at what’s in the species table. It’s a table of the species_id and the full genus, species and taxa information for each species_id. Having this in a separate table is nice, because we didn’t need to include all this information in our main surveys table.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM species;Now let’s order it by taxa.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM species

ORDER BY taxa ASC;The keyword ASC tells us to order it in ascending order.

We could alternately use DESC to get descending order.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM species

ORDER BY taxa DESC;ASC is the default.

We can also sort on several fields at once. To truly be alphabetical, we might want to order by genus then species.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM species

ORDER BY genus ASC, species ASC;SQL

SELECT year, species_id, weight / 1000

FROM surveys

ORDER BY weight DESC;Order of execution

Another note for ordering. We don’t actually have to display a column to sort by it. For example, let’s say we want to order the birds by their species ID, but we only want to see genus and species.

SQL

SELECT genus, species

FROM species

WHERE taxa = 'Bird'

ORDER BY species_id ASC;We can do this because sorting occurs earlier in the computational pipeline than field selection.

The computer is basically doing this:

- Filtering rows according to WHERE

- Sorting results according to ORDER BY

- Displaying requested columns or expressions.

Clauses are written in a fixed order: SELECT,

FROM, WHERE, then ORDER BY.

Challenge

- Let’s try to combine what we’ve learned so far in a single query.

Using the surveys table, write a query to display the three date fields,

species_id, and weight in kilograms (rounded to two decimal places), for individuals captured in 1999, ordered alphabetically by thespecies_id. - Write the query as a single line, then put each clause on its own line, and see how more legible the query becomes!

SQL

SELECT year, month, day, species_id, ROUND(weight / 1000, 2)

FROM surveys

WHERE year = 1999

ORDER BY species_id;Keypoints

- It is useful to apply conventions when writing SQL queries to aid readability.

- Use logical connectors such as AND or OR to create more complex queries.

- Calculations using mathematical symbols can also be performed on SQL queries.

- Adding comments in SQL helps keep complex queries understandable.

Content from Aggregating and Grouping Data

Last updated on 2023-04-21 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I summarize my data by aggregating, filtering, or ordering query results?

- How can I make sure column names from my queries make sense and aren’t too long?

Objectives

- Apply aggregation functions to group records together.

- Filter and order results of a query based on aggregate functions.

- Employ aliases to assign new names to items in a query.

- Save a query to make a new table.

- Apply filters to find missing values in SQL.

COUNT and GROUP BY

Aggregation allows us to combine results by grouping records based on value. It is also useful for calculating combined values in groups.

Let’s go to the surveys table and find out how many individuals there are. Using the wildcard * counts the number of records (rows):

SQL

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM surveys;We can also find out how much all of those individuals weigh:

SQL

SELECT COUNT(*), SUM(weight)

FROM surveys;We can output this value in kilograms (dividing the value by 1000.00), then rounding to 3 decimal places: (Notice the divisor has numbers after the decimal point, which forces the answer to have a decimal fraction)

SQL

SELECT ROUND(SUM(weight)/1000.00, 3)

FROM surveys;There are many other aggregate functions included in SQL, for

example: MAX, MIN, and AVG.

SQL

-- All animals

SELECT SUM(weight), AVG(weight), MIN(weight), MAX(weight)

FROM surveys;

-- Only weights between 5 and 10

SELECT SUM(weight), AVG(weight), MIN(weight), MAX(weight)

FROM surveys

WHERE (weight > 5) AND (weight < 10);Now, let’s see how many individuals were counted in each species. We

do this using a GROUP BY clause

SQL

SELECT species_id, COUNT(*)

FROM surveys

GROUP BY species_id;GROUP BY tells SQL what field or fields we want to use

to aggregate the data. If we want to group by multiple fields, we give

GROUP BY a comma separated list.

SQL

SELECT year, COUNT(*)

FROM surveys

GROUP BY year;SQL

SELECT year, species_id, COUNT(*), AVG(weight)

FROM surveys

GROUP BY year, species_id;Ordering Aggregated Results

We can order the results of our aggregation by a specific column, including the aggregated column. Let’s count the number of individuals of each species captured, ordered by the count:

SQL

SELECT species_id, COUNT(*)

FROM surveys

GROUP BY species_id

ORDER BY COUNT(species_id);Aliases

As queries get more complex, the expressions we use can get long and unwieldy. To help make things clearer in the query and in its output, we can use aliases to assign new names to things in the query.

We can use aliases in column names using AS:

SQL

SELECT MAX(year) AS last_surveyed_year

FROM surveys;The AS isn’t technically required, so you could do

SQL

SELECT MAX(year) last_surveyed_year

FROM surveys;but using AS is much clearer so it is good style to

include it.

We can not only alias column names, but also table names in the same way:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys AS surv;And again, the AS keyword is not required, so this

works, too:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys surv;Aliasing table names can be helpful when working with queries that involve multiple tables; you will learn more about this later.

The HAVING keyword

In the previous episode, we have seen the keyword WHERE,

allowing to filter the results according to some criteria. SQL offers a

mechanism to filter the results based on aggregate

functions, through the HAVING keyword.

For example, we can request to only return information about species with a count higher than 10:

SQL

SELECT species_id, COUNT(species_id)

FROM surveys

GROUP BY species_id

HAVING COUNT(species_id) > 10;The HAVING keyword works exactly like the

WHERE keyword, but uses aggregate functions instead of

database fields to filter.

You can use the AS keyword to assign an alias to a

column or table, and refer to that alias in the HAVING

clause. For example, in the above query, we can call the

COUNT(species_id) by another name, like

occurrences. This can be written this way:

SQL

SELECT species_id, COUNT(species_id) AS occurrences

FROM surveys

GROUP BY species_id

HAVING occurrences > 10;Note that in both queries, HAVING comes after

GROUP BY. One way to think about this is: the data are

retrieved (SELECT), which can be filtered

(WHERE), then joined in groups (GROUP BY);

finally, we can filter again based on some of these groups

(HAVING).

SQL

SELECT taxa, COUNT(*) AS n

FROM species

GROUP BY taxa

HAVING n > 10;Saving Queries for Future Use

It is not uncommon to repeat the same operation more than once, for example for monitoring or reporting purposes. SQL comes with a very powerful mechanism to do this by creating views. Views are a form of query that is saved in the database, and can be used to look at, filter, and even update information. One way to think of views is as a table, that can read, aggregate, and filter information from several places before showing it to you.

Creating a view from a query requires us to add

CREATE VIEW viewname AS before the query itself. For

example, imagine that our project only covers the data gathered during

the summer (May - September) of 2000. That query would look like:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

WHERE year = 2000 AND (month > 4 AND month < 10);But we don’t want to have to type that every time we want to ask a question about that particular subset of data. Hence, we can benefit from a view:

SQL

CREATE VIEW summer_2000 AS

SELECT *

FROM surveys

WHERE year = 2000 AND (month > 4 AND month < 10);Using a view we will be able to access these results with a much shorter notation:

SQL

SELECT *

FROM summer_2000

WHERE species_id = 'PE';What About NULL?

From the last example, there should only be five records. If you look

at the weight column, it’s easy to see what the average

weight would be. If we use SQL to find the average weight, SQL behaves

like we would hope, ignoring the NULL values:

SQL

SELECT AVG(weight)

FROM summer_2000

WHERE species_id = 'PE';But if we try to be extra clever, and find the average ourselves, we might get tripped up:

SQL

SELECT SUM(weight), COUNT(*), SUM(weight)/COUNT(*)

FROM summer_2000

WHERE species_id = 'PE';Here the COUNT function includes all five records (even

those with NULL values), but the SUM only includes the

three records with data in the weight field, giving us an

incorrect average. However, our strategy will work if we modify

the COUNT function slightly:

SQL

SELECT SUM(weight), COUNT(weight), SUM(weight)/COUNT(weight)

FROM summer_2000

WHERE species_id = 'PE';When we count the weight field specifically, SQL ignores the records

with data missing in that field. So here is one example where NULLs can

be tricky: COUNT(*) and COUNT(field) can

return different values.

Another case is when we use a “negative” query. Let’s count all the non-female animals:

SQL

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM summer_2000

WHERE sex != 'F';Now let’s count all the non-male animals:

SQL

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM summer_2000

WHERE sex != 'M';But if we compare those two numbers with the total:

SQL

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM summer_2000;We’ll see that they don’t add up to the total! That’s because SQL doesn’t automatically include NULL values in a negative conditional statement. So if we are querying “not x”, then SQL divides our data into three categories: ‘x’, ‘not NULL, not x’ and NULL; then, returns the ‘not NULL, not x’ group. Sometimes this may be what we want - but sometimes we may want the missing values included as well! In that case, we’d need to change our query to:

SQL

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM summer_2000

WHERE sex != 'M' OR sex IS NULL;Keypoints

- Use the

GROUP BYkeyword to aggregate data. - Functions like

MIN,MAX,AVG,SUM,COUNT, etc. operate on aggregated data. - Aliases can help shorten long queries. To write clear and readable

queries, use the

ASkeyword when creating aliases. - Use the

HAVINGkeyword to filter on aggregate properties. - Use a

VIEWto access the result of a query as though it was a new table.

Content from Combining Data With Joins

Last updated on 2023-06-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do I bring data together from separate tables?

Objectives

- Employ joins to combine data from two tables.

- Apply functions to manipulate individual values.

- Employ aliases to assign new names to tables and columns in a query.

Joins

To combine data from two tables we use an SQL JOIN

clause, which comes after the FROM clause.

Database tables are used to organize and group data by common

characteristics or principles.

Often, we need to combine elements from separate tables into a single

tables or queries for analysis and visualization. A JOIN is a means for

combining columns from multiple tables by using values common to

each.

The JOIN keyword combined with ON is used to combine fields from separate tables.

A JOIN clause on its own will result in a cross product,

where each row in the first table is paired with each row in the second

table. Usually this is not what is desired when combining two tables

with data that is related in some way.

For that, we need to tell the computer which columns provide the link

between the two tables using the word ON. What we want is

to join the data with the same species id.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

JOIN species

ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id;ON is like WHERE. It filters things out

according to a test condition. We use the table.colname

format to tell the manager what column in which table we are referring

to.

The output from using the JOIN clause will have columns

from the first table plus the columns from the second table. For the

above statement, the output will be a table that has the following

column names:

| record_id | month | day | year | plot_id | species_id | sex | hindfoot_length | weight | species_id | genus | species | taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| … | ||||||||||||

| 96 | 8 | 20 | 1997 | 12 | DM | M | 36 | 41 | DM | Dipodomys | merriami | Rodent |

| … |

Alternatively, we can use the word USING, as a

short-hand. USING only works on columns which share the

same name. In this case we are telling the manager that we want to

combine surveys with species and that the

common column is species_id.

SQL

SELECT *

FROM surveys

JOIN species

USING (species_id);The output will only have one species_id column

| record_id | month | day | year | plot_id | species_id | sex | hindfoot_length | weight | genus | species | taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| … | |||||||||||

| 96 | 8 | 20 | 1997 | 12 | DM | M | 36 | 41 | Dipodomys | merriami | Rodent |

| … |

We often won’t want all of the fields from both tables, so anywhere

we would have used a field name in a non-join query, we can use

table.colname.

For example, what if we wanted information on when individuals of each species were captured, but instead of their species ID we wanted their actual species names.

SQL

SELECT surveys.year, surveys.month, surveys.day, species.genus, species.species

FROM surveys

JOIN species

ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id;| year | month | day | genus | species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| … | ||||

| 1977 | 7 | 16 | Neotoma | albigula |

| 1977 | 7 | 16 | Dipodomys | merriami |

| … |

Many databases, including SQLite, also support a join through the

WHERE clause of a query.

For example, you may see the query above written without an explicit

JOIN.

SQL

SELECT surveys.year, surveys.month, surveys.day, species.genus, species.species

FROM surveys, species

WHERE surveys.species_id = species.species_id;For the remainder of this lesson, we’ll stick with the explicit use

of the JOIN keyword for joining tables in SQL.

SQL

SELECT species.genus, species.species, surveys.weight

FROM surveys

JOIN species

ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id;Different join types

We can count the number of records returned by our original join query.

SQL

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM surveys

JOIN species

USING (species_id);Notice that this number is smaller than the number of records present in the survey data.

SQL

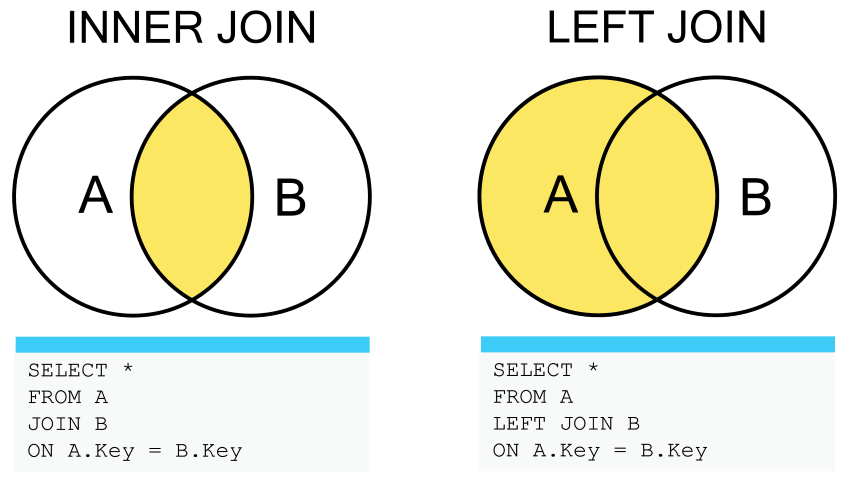

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM surveys;This is because, by default, SQL only returns records where the

joining value is present in the joined columns of both tables (i.e. it

takes the intersection of the two join columns). This joining

behaviour is known as an INNER JOIN. In fact the

JOIN keyword is simply shorthand for

INNER JOIN and the two terms can be used interchangeably as

they will produce the same result.

We can also tell the computer that we wish to keep all the records in

the first table by using a LEFT OUTER JOIN clause, or

LEFT JOIN for short. The difference between the two JOINs

can be visualized like so:

SQL

SELECT * FROM surveys

LEFT JOIN species

USING (species_id);SQL

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM surveys

WHERE species_id IS NULL;Remember: In SQL a NULL value in one table can never be

joined to a NULL value in a second table because

NULL is not equal to anything, not even itself.

Combining joins with sorting and aggregation

Joins can be combined with sorting, filtering, and aggregation. So, if we wanted average mass of the individuals on each different type of treatment, we could do something like

SQL

SELECT plots.plot_type, AVG(surveys.weight)

FROM surveys

JOIN plots

ON surveys.plot_id = plots.plot_id

GROUP BY plots.plot_type;SQL

SELECT surveys.plot_id, species.genus, COUNT(*) AS number_indiv

FROM surveys

JOIN species

ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id

GROUP BY species.genus, surveys.plot_id

ORDER BY surveys.plot_id ASC, number_indiv DESC;SQL

SELECT surveys.species_id, AVG(surveys.weight)

FROM surveys

JOIN species

ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id

WHERE species.taxa = 'Rodent'

GROUP BY surveys.species_id;Functions COALESCE and NULLIF and

more

SQL includes numerous functions for manipulating data. You’ve already

seen some of these being used for aggregation (SUM and

COUNT) but there are functions that operate on individual

values as well. Probably the most important of these are

COALESCE and NULLIF. COALESCE

allows us to specify a value to use in place of NULL.

We can represent unknown sexes with 'U' instead of

NULL:

SQL

SELECT species_id, sex, COALESCE(sex, 'U')

FROM surveys;The lone “sex” column is only included in the query above to

illustrate where COALESCE has changed values; this isn’t a

usage requirement.

SQL

SELECT hindfoot_length, COALESCE(hindfoot_length, 30)

FROM surveys;SQL

SELECT species_id, AVG(COALESCE(hindfoot_length, 30))

FROM surveys

GROUP BY species_id;COALESCE can be particularly useful in

JOIN. When joining the species and

surveys tables earlier, some results were excluded because

the species_id was NULL in the surveys table.

We can use COALESCE to include them again, re-writing the

NULL to a valid joining value:

SQL

SELECT surveys.year, surveys.month, surveys.day, species.genus, species.species

FROM surveys

JOIN species

ON COALESCE(surveys.species_id, 'AB') = species.species_id;SQL

SELECT plot_id, COALESCE(genus, 'Rodent') AS genus2, COUNT(*)

FROM surveys

LEFT JOIN species

ON surveys.species_id=species.species_id

GROUP BY plot_id, genus2;The inverse of COALESCE is NULLIF. This

returns NULL if the first argument is equal to the second

argument. If the two are not equal, the first argument is returned. This

is useful for “nulling out” specific values.

We can “null out” plot 7:

SQL

SELECT species_id, plot_id, NULLIF(plot_id, 7)

FROM surveys;Some more functions which are common to SQL databases are listed in the table below:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

ABS(n) |

Returns the absolute (positive) value of the numeric expression n |

COALESCE(x1, ..., xN) |

Returns the first of its parameters that is not NULL |

LENGTH(s) |

Returns the length of the string expression s |

LOWER(s) |

Returns the string expression s converted to lowercase |

NULLIF(x, y) |

Returns NULL if x is equal to y, otherwise returns x |

ROUND(n) or ROUND(n, x)

|

Returns the numeric expression n rounded to x digits after the decimal point (0 by default) |

TRIM(s) |

Returns the string expression s without leading and trailing whitespace characters |

UPPER(s) |

Returns the string expression s converted to uppercase |

Finally, some useful functions which are particular to SQLite are listed in the table below:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

RANDOM() |

Returns a random integer between -9223372036854775808 and +9223372036854775807. |

REPLACE(s, f, r) |

Returns the string expression s in which every occurrence of f has been replaced with r |

SUBSTR(s, x, y) or SUBSTR(s, x)

|

Returns the portion of the string expression s starting at the character position x (leftmost position is 1), y characters long (or to the end of s if y is omitted) |

SQL

SELECT DISTINCT genus

FROM species

ORDER BY LENGTH(genus) DESC;As we saw before, aliases make things clearer, and are especially useful when joining tables.

SQL

SELECT surv.year AS yr, surv.month AS mo, surv.day AS day, sp.genus AS gen, sp.species AS sp

FROM surveys AS surv

JOIN species AS sp

ON surv.species_id = sp.species_id;To practice we have some optional challenges for you.

Challenge (optional):

SQL queries help us ask specific questions which we want to answer about our data. The real skill with SQL is to know how to translate our scientific questions into a sensible SQL query (and subsequently visualize and interpret our results).

Have a look at the following questions; these questions are written in plain English. Can you translate them to SQL queries and give a suitable answer?

How many plots from each type are there?

How many specimens are of each sex are there for each year, including those whose sex is unknown?

How many specimens of each species were captured in each type of plot, excluding specimens of unknown species?

What is the average weight of each taxa?

What are the minimum, maximum and average weight for each species of Rodent?

What is the average hindfoot length for male and female rodent of each species? Is there a Male / Female difference?

What is the average weight of each rodent species over the course of the years? Is there any noticeable trend for any of the species?

- Solution:

SQL

SELECT plot_type, COUNT(*) AS num_plots

FROM plots

GROUP BY plot_type;- Solution:

SQL

SELECT year, sex, COUNT(*) AS num_animal

FROM surveys

GROUP BY sex, year;- Solution:

SQL

SELECT species_id, plot_type, COUNT(*)

FROM surveys

JOIN plots USING(plot_id)

WHERE species_id IS NOT NULL

GROUP BY species_id, plot_type;- Solution:

SQL

SELECT taxa, AVG(weight)

FROM surveys

JOIN species ON species.species_id = surveys.species_id

GROUP BY taxa;- Solution:

SQL

SELECT surveys.species_id, MIN(weight), MAX(weight), AVG(weight) FROM surveys

JOIN species ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id

WHERE taxa = 'Rodent'

GROUP BY surveys.species_id;- Solution:

SQL

SELECT surveys.species_id, sex, AVG(hindfoot_length)

FROM surveys JOIN species ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id

WHERE (taxa = 'Rodent') AND (sex IS NOT NULL)

GROUP BY surveys.species_id, sex;- Solution:

SQL

SELECT surveys.species_id, year, AVG(weight) as mean_weight

FROM surveys

JOIN species ON surveys.species_id = species.species_id

WHERE taxa = 'Rodent' GROUP BY surveys.species_id, year;Keypoints

- Use a

JOINclause to combine data from two tables—theONorUSINGkeywords specify which columns link the tables. - Regular

JOINreturns only matching rows. Other join clauses provide different behavior, e.g.,LEFT JOINretains all rows of the table on the left side of the clause. -

COALESCEallows you to specify a value to use in place ofNULL, which can help in joins -

NULLIFcan be used to replace certain values withNULLin results - Many other functions like

COALESCEandNULLIFcan operate on individual values.